Will batteries be the limiting factor for heavy-duty electrification?

Context

It is broadly assumed that electrification of commercial vehicles will lag that of passenger cars. And for some good reasons. First and foremost, trucks are not bigger cars, but tools for delivering goods, while making profit for the service provider. Low cost, uptime and ability to carry the highest allowable payload are therefore of paramount importance. These translate into various requirements specific to the trucking sector that need to be addressed before electrification can take off in a meaningful way.

This short post examines one of the issues – whether batteries can be a limiting factor, especially when compared to the competing requirements from the light-duty or passenger car fleet.

Driving range vs. Battery capacity

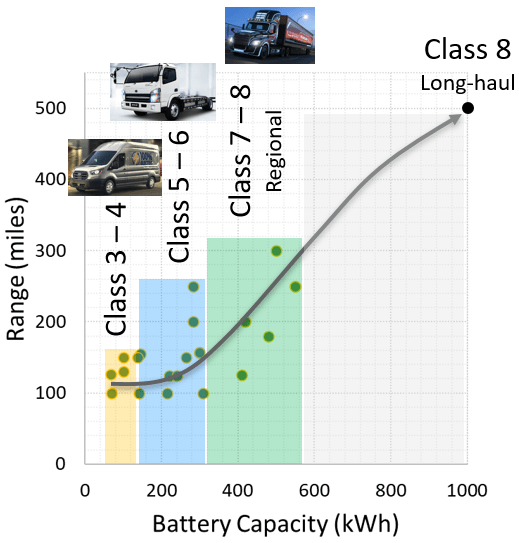

Various OEMs have introduced or announced electric vehicles in the Class 3 – 8 segments. The figure here shows the promised range as a function of the battery size. This is not a comprehensive summary but a representative one including leading manufacturers / models. Two observations:

What is seen is that there are a lot of offering in the 100 – 300 kWh battery size segments, and also a few which cover larger trucks aimed at regional distribution, refuse pickup and other vocational needs. These cover a large fraction (~75%) of the heavy-duty needs today. And these are relatively easier to charge : a 300 kWh battery can be charged in 2 hours with a 150 kW DC charger, available today, and can be done overnight and between stops.

What is missing is offerings in the long-haul segment. These are the trucks which travel all day and can transport goods over 500 miles to the end distribution centers. A simple extrapolation shows that such a truck would need ~ 1 MWh of batteries. And this would require some serious thinking in terms of the charging infrastructure for obvious reasons. Also, the battery weight itself would be around 10,000 lbs. and this starts reducing the payload capacity of the trucks. (Note that in Europe, there is a 2 ton or 4,000 lbs. extra allowance being given to electric trucks).

How much batteries do we need ?

Taking the average battery capacities in each of the Class 3 – 8 segment and knowing the annual sales (we have used Statista), here is the projection of the battery requirements. The green bar is what would be the requirement for Class 8 if 25% of the vehicles in that class were 1MWh batteries with a 500 mile range.

So what is the point here? Well, if you add up all of the bars, using the green for Class 8, we get 219 GWh of batteries per year to meet the entire US HD fleet requirement.

That is 15% of the requirement for converting the entire US light-duty fleet to fully electric vehicles (17 million vehicles sold each year, assuming each with a 85 kWh battery = 1.4TWh battery requirement).

Which suggests that battery capacity is NOT going to be the limiting factor when it comes to heavy-duty electrification. After all, 219 GWh translates to ~ 6 Gigafactories, which could be done easily, given the pace of battery announcements made each day.

So should we expect all trucks to be electrified soon?

Not so fast. Also depends on your definition of “soon”. There are various factors that need to be addressed before we see fleet owners lining up for electrics:

(1) Total cost of ownership is key. Electric vehicles cost much more than diesels (> 2X), and the gap will reduce with time and volume.

(2) Charging infrastructure : this is in its infancy compared to the light-duty sector, and as mentioned above, we will also need upgrades to the hardware to deliver faster charging rates for large batteries.

(3) Sufficient driving range (with payload) – this gets back to managing cost and charging for larger batteries. Alternatively, this could mean new business models and innovative thinking on transporting goods (the “hub-and-spoke” model for instance). Autonomous driving can also ease some of the requirements here, but that is a separate topic and not without its challenges.

(4) Trained drivers, maintenance, durability – these other issues which are not typically addressed when we think of electrification, but will rear their heads when we get to more meaningful penetration of electric trucks.

(5) Competing technologies – diesels are getting cleaner and more efficient. They will not go down without a serious fight. And then there are other alternatives being explored : renewable and synthetics fuels, hybridized powertrains, fuel cell trucks, hydrogen ICE etc. which could add to the choices for modern fleets.

Finally, will it help?

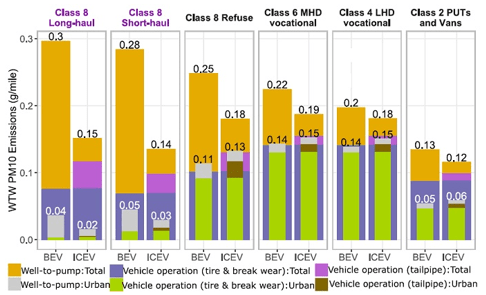

Not to lose sight of the bigger goal here : the whole point of electrification is to reduce greenhouse gas and criteria pollutant emissions. As the grid gets cleaner, that objective will be met, but we have some work to do on that front. Diesel trucks will reduce fuel consumption significantly by the end of this decade to comply with regulations in the US and Europe. NOx emissions are expected to go down by 90% and particulate emissions will reduce by 50% below already low values, also by the end of this decade. Both of these mean a moving and tougher target for electrics.

The case in point is a recent analysis done by researchers at Argonne National Lab, which shows that when converted to electrics, net particulate emissions from the heavy-duty fleet could actually increase due to upstream emissions from the power plants (this was for a 2030 grid). Also, CO2 emissions were shown to reduce on average by 15%, but could also increase by as much as 25% across some of the local grids across the country.

None of this is meant to be a pessimistic view on electrification or other technologies. Rather, as the post suggests, some of the barriers may be lower than we think. But others are going to require some innovative approaches and careful policy thinking. In any case, this should be an exciting decade as we navigate these challenges.

From “Well-to-Wheels Analysis of Zero-Emission Plug-In Battery Electric Vehicle Technology for Medium- and Heavy-Duty Trucks”, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.0c02931

Check out the monthly newsletter covering the latest on sustainable transportation technologies and regulations. Sign up if you like such content.

Like it ? Share it !

Other recent posts

EPA Demands Manufacturer Data as It Expands Action on DEF System Failures

![]()

A brief summary of recent EPA changes to DEF-related failures.

EPA repeals 2009 GHG endangerment finding

![]()

The US EPA is repealing the 2009 GHG endangerment finding and terminating all vehicular GHG standards.

Efficiency of EVs in US and China

![]()

China has set energy efficiency norms for electric vehicles – how do modern EVs fare?